Understanding the Kimwolf Botnet and Its Silent Invasion of Home Networks via IoT Devices

Kimwolf botnet exploits insecure IoT devices and residential proxies to infiltrate home networks. Learn how it spreads and how to protect your devices.

The Kimwolf botnet is a rapidly expanding global cyber threat, now infecting more than two million devices. Its most alarming capability is its ability to infiltrate private home networks by exploiting residential proxy systems and insecure IoT devices. This report highlights how Kimwolf works, why it spreads so quickly, and what consumers can do to protect themselves.

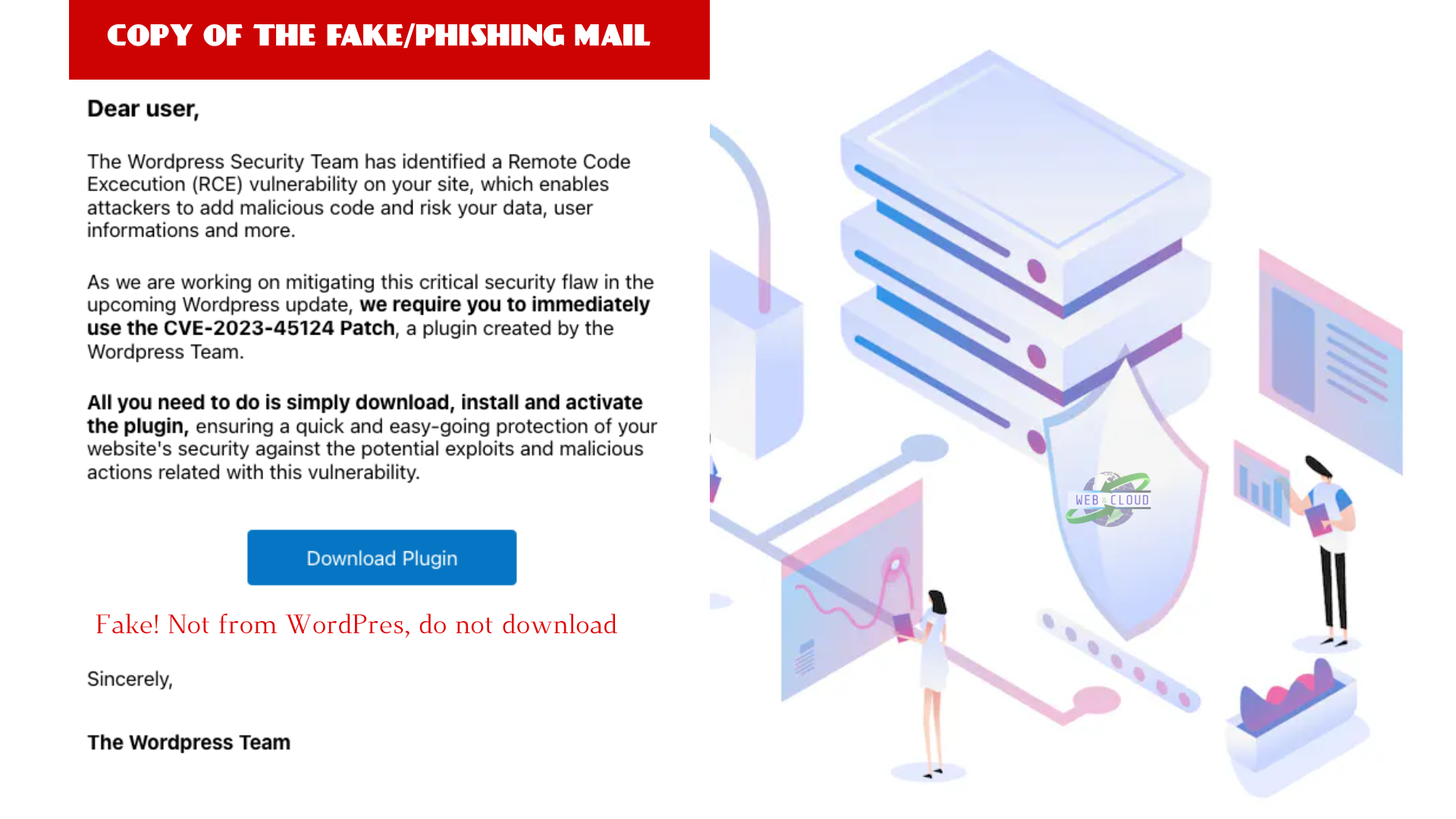

What Is the Kimwolf Botnet?

Kimwolf is a large-scale botnet targeting Android-based IoT devices such as Android TV boxes and digital photo frames. Once infected, these devices are used for ad fraud, account takeover attempts, content scraping, and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. The botnet has already surpassed two million infections, with major concentrations in Vietnam, Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the United States.

A significant portion of infected devices are low-cost Android TV boxes that lack authentication, security controls, and proper firmware protections.

How Kimwolf Spreads Through Residential Proxy Networks

Kimwolf leverages weaknesses in residential proxy networks—systems that route traffic through real users’ devices. Many users unknowingly become proxy nodes by installing untrusted mobile apps or using Android TV boxes preloaded with malicious software. These devices often rely on unofficial app stores, increasing exposure to malware.

A critical flaw allowed proxy providers to resolve internal LAN addresses through DNS. This loophole enabled attackers to tunnel into private home networks, scan for vulnerable devices, and silently install malware.

The Role of Android TV Boxes and Digital Photo Frames

Many low-cost Android devices share two major security issues: pre-installed malware and Android Debug Bridge (ADB) access enabled by default. ADB provides full administrative control without authentication, allowing attackers to compromise devices simply by reaching them over the local network.

Kimwolf operators exploit this by tunneling through residential proxies, scanning internal networks, and installing malware on any device with open ADB ports.

Discovery by Synthient and Researcher Benjamin Brundage

Benjamin Brundage, founder of Synthient, uncovered Kimwolf’s rapid expansion and its reliance on ADB-enabled devices. His research revealed a near-perfect overlap between Kimwolf infections and endpoints associated with the proxy provider IPIDEA. Brundage alerted multiple proxy providers in December 2025, urging them to patch the vulnerability before public disclosure.

IPIDEA’s Response

IPIDEA initially denied involvement but later acknowledged that a legacy module allowed internal network access. The company implemented fixes, including blocking DNS resolution for internal IP ranges and restricting high-risk ports. Other proxy providers, such as Oxylabs, also applied similar mitigations.

Connection to the 911S5 Proxy Network

Researchers noted similarities between IPIDEA and the notorious 911S5 Proxy network, which operated from 2014 to 2022 and was widely used by cybercriminals. After its collapse, U.S. authorities linked 911S5 to Chinese operators. IPIDEA also runs a service called 922 Proxy, raising further suspicion due to the naming resemblance.

Implications for Home Users

Kimwolf demonstrates that home networks are no longer inherently safe. A single infected guest device can expose an entire household to attack. Once inside the network, Kimwolf can compromise IoT devices, alter router DNS settings, and hijack browsing sessions. This mirrors the widespread DNSChanger malware outbreak from 2012.

Findings from XLab

Chinese cybersecurity firm XLab independently tracked Kimwolf and confirmed its scale, estimating between 1.8 and 2 million infected devices. They observed heavy activity in Brazil, India, the United States, and Argentina. Kimwolf frequently topped Cloudflare’s DNS traffic charts and demonstrated the ability to rebuild itself quickly after takedowns.

XLab also discovered references to Brian Krebs embedded within the botnet’s code, suggesting the author intentionally left behind “easter eggs.”

What Consumers Can Do

Most users lack the tools to detect Kimwolf infections, but Synthient provides a public checker to determine whether an IP address has been associated with botnet activity. They also published a list of high-risk Android TV boxes known to be vulnerable.

Recommended actions include removing any device on the high-risk list, using guest Wi-Fi networks for visitors, avoiding no-name Android TV boxes, and sticking to trusted brands. Users should also be cautious with mobile apps and avoid unofficial app stores.

Broader Context: BADBOX 2.0 and FBI Warnings

The FBI and Google have warned about BADBOX 2.0, a botnet of more than ten million compromised Android devices. Many of these devices are infected before purchase or during setup through malicious app stores. These botnets fuel ad fraud, ticket scalping, retail fraud, account takeovers, and content scraping.

Kimwolf fits into this broader trend of malicious IoT supply chains and highlights the growing threat posed by insecure consumer electronics.

Final Takeaway

Kimwolf is a clear warning that home networks are no longer safe by default. Residential proxy networks, insecure IoT devices, and ADB-enabled hardware have created an environment where attackers can bypass firewalls, infiltrate private networks, and build massive botnets with ease. This is only the first part of the investigation, with future reporting expected to explore who created Kimwolf and who benefits from its operations.

Reward this post with your reaction or TipDrop:

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

TipDrop

0

TipDrop

0